If people have the choice to pay for something, or to be a free rider, almost everyone will choose to be a free rider. There are other aspects, which (I think) has not been mentioned by other answers. There are many other contexts in which "free riding" does not represent exactly the same situation, and as a consequence the potential solution for the game will be different. In this "coward game", A or B WILL pay for the machine, even knowing that the other will behave as a free rider, because the alternative (not building the machine) is worse not only for the free rider (which would use the public good for free), but also for the city which will build the machine, since they both have a big pollution problem. In this case, those 2 cities do not represent the same kind of potential free riders as in the street lights example, since in this case both cities need to do something. This would solve the problem for both cities, even in the case that just one of them paid for it. The problem could be solved with a single machine next to the river. This pollution is causing diseases in the population, so both cities are "losing", in public terms. However, let's imagine this example: 2 cities, A and B, which are dumping pollution in a shared river. But if they do not buy them, nobody will lose anything (except the opportunity of having that extra profit). In the example cited by him about street lights, it is quite obvious that people there could get an extra profit thanks to those lights. I would also add to answer that not all free riders play the exact same role in every situation.

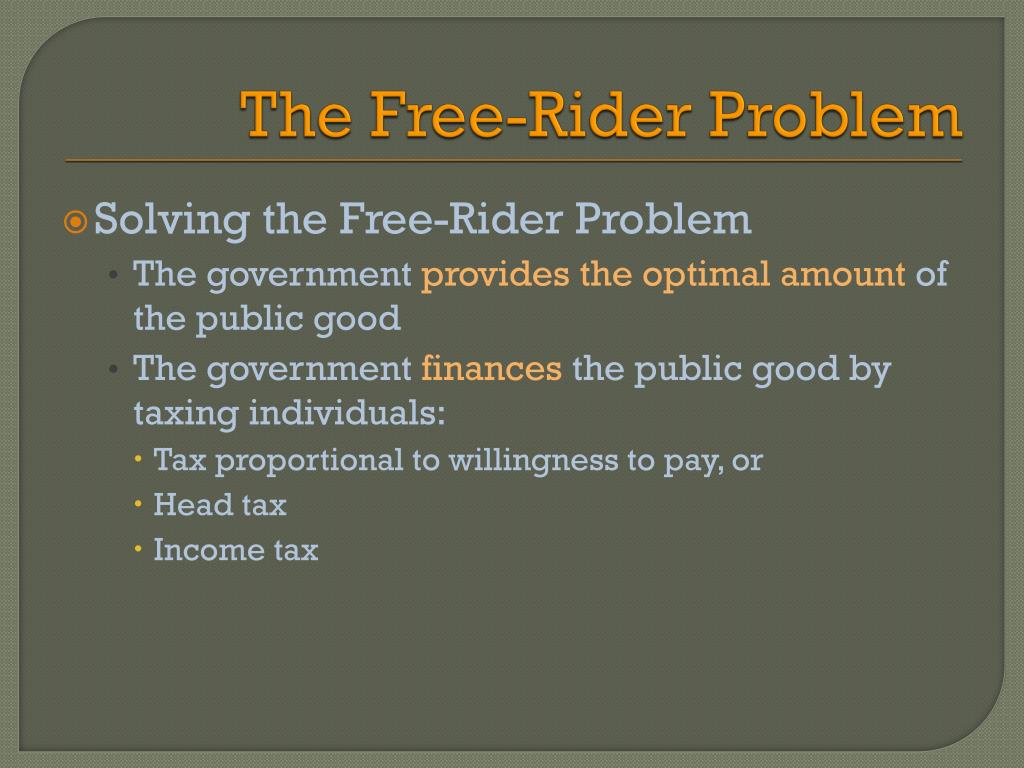

Rather, the problem is that, since people are expected to free ride, the park won't be created in the first place. To use your example of parks, the problem is not that people get to use the park without paying. I should stress that, from the perspective of Pareto efficiency, the problem with 'free riding' has nothing to do with 'equity'. If the inhabitants could be compelled to pay for the street light, sharing the cost equally, then they would all be better off. That's a problem since the total benefit (10 x £100 = £1000) greatly exceeds the cost of the light. Although any resident would benefit from the street light, building it would cost them £101, which exceeds the benefit (£100).

Will it be produced? If people are self-interested, then the answer is no. The street light would cost £101 to produce, but if produced can be used by all for free: this is known as 'non-excludability'. each would pay up to £100 to bring a new street light into existence). To illustrate using a standard example, suppose that 10 people live on a street, and that each would value an additional street light at £100 (i.e. That means that we are forfeiting an opportunity to help people without harming anyone else. According to the standard criterion used to evaluate welfare (Pareto efficiency), the problem with 'free riding' is that goods are not produced even though they cost less to produce than they are worth to consumers.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)